Why The New York Times Said "No" to Apple News

- 2019年4月29日

- 讀畢需時 7 分鐘

已更新:2025年11月23日

(This is the English translation of a news story written for Caixin Weekly magazine.

It was originally in Chinese with another summarized English version published for Caixin Global.

The Chinese version is as follows:

The summarized English version is as follows:

https://www.caixinglobal.com/2019-04-29/why-the-new-york-times-said-no-to-apple-news-101409816.html)

In an exclusive interview with Caixin, Mark Thompson, President and CEO of The New York Times, discussed collaboration and competition between legacy media and technology companies.

Mark Thompson pulled an Android phone from his suit pocket, displaying a device loaded with apps from major global news publishers: The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Economist, and The Guardian, among others. “If you take news seriously enough, you should obtain different perspectives from different publishers,” he said.

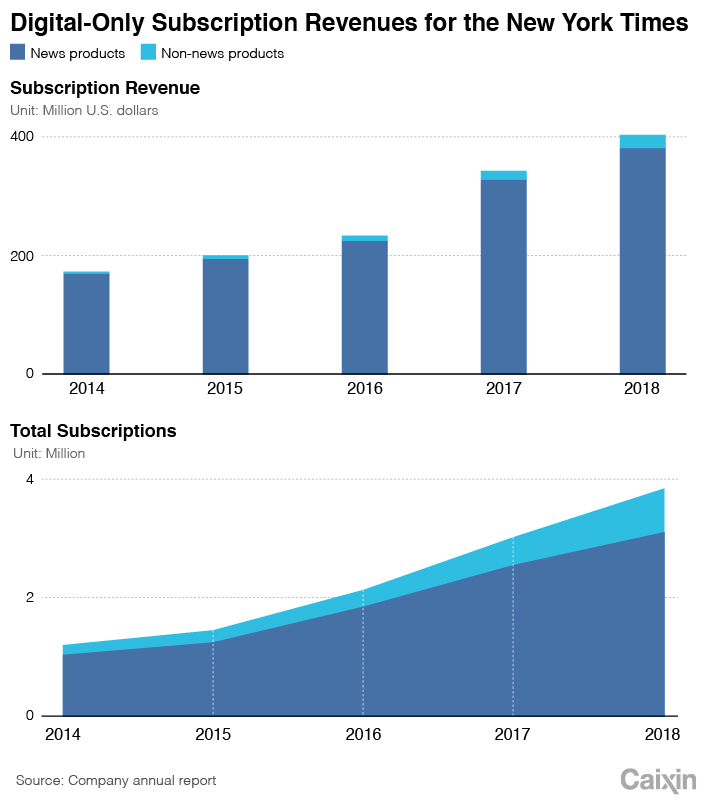

Having spent 33 years at the BBC, the 62-year-old Thompson became President and CEO of The New York Times in 2012, where he immediately spearheaded the paper's digital transformation. Under his tenure, digital subscriptions have surged fourfold. However, Apple’s recent launch of its news subscription service has sparked significant concern and a sharp backlash from media companies, including The Times.

Product: The Distruptor of Journalism

Apple News+ gained over 200,000 subscribers within 48 hours of its launch, according to figures obtained by The Times from internal sources. Apple unveiled the service—an upgraded news aggregation app offering users access to content from more than 300 publishers across all Apple devices for a low monthly fee—at its annual product event in March.

Since the era of Steve Jobs, Apple has sought to be the "savior of journalism." The Silicon Valley giant believes its vast user base can help struggling print media grow their audience and subscriptions. As the service evolved from a previously acquired magazine aggregator, most of Apple News+'s partners are magazines. Yet, surprisingly, three mainstream newspapers also signed on: The Wall Street Journal, the Los Angeles Times, and the Toronto Star, Canada's largest daily .

All three newspapers cited the partnership as a means to expand their subscriber base and generate new income streams, though details were not disclosed. The LA Times, which currently has just 150,000 digital subscribers, is aiming for five million in the long term. Both The Wall Street Journal and the Toronto Star hoped to reach new readers through Apple’s platform.

However, The New York Times and The Washington Post declined to participate. These legacy media outlets expressed concern that, this time, Apple was not a "savior" but a "disruptor."

Content: Human Judgment Over Algorithms

The New York Times has a history of collaboration with tech giants like Google and Facebook, and it was an early partner when the original Apple News platform launched in 2015. However, this history does not mean the paper is fully on board with Apple’s current approach to reshaping the news industry.

Thompson argued that Apple’s news aggregation service poses serious problems, particularly due to the mixed blend of content from different outlets. “News isn’t like music. When people listen to music, they care about the song, not the platform. But with news, who made it and whether you can trust it matters,” said Thompson, adding that fake news often hides among real news, and mixing everything together makes it harder for readers to tell truth from fiction.

Concerns over content authenticity are not the only issue; algorithms also pose a challenge to traditional newsrooms. Today, new media and tech companies track user preferences via algorithms, pushing more related content directly to them. This user-centered strategy, however, threatens the legacy media’s traditional role in setting the public agenda.

“I think the top stories featured on the homepage of a news app should be selected by people rather than artificial intelligence,” Thompson said as he quickly opened the Times app and pointed to the screen.

Balancing what readers should know and what they like to read is never easy. Thompson insisted that the significance of a story must be decided by human editors, not algorithms. “Our job isn’t to give readers the most ‘sexy’ stories, but to decide what matters most,” he said.

Distribution: Fear of Disrupted Business Models

It is evident that tech platforms can significantly unlock the potential of content distribution. While news organizations want to leverage this power to reach broader audiences, they also fear losing control over their own destiny. For many, the crucial decision is whether to run their “own stores” or rely on external “distributors.”

“We want our news to reach as many people as possible, but we’d rather readers get used to using our own app,” said Thompson. Prior to the launch of Apple News+, he warned in a Reuters interview that the service’s business model could monopolize content distribution, citing Netflix as a cautionary example.

Thompson’s concern was well-founded. In the U.S. cable TV industry, Netflix played a similar role to what Apple is doing now. The streaming service initially paid significant fees to license content from major cable television networks and aggregated it on its own platform. Over time, viewers relied more on the content aggregator while caring less about the source of the shows. Once Netflix had amassed enough loyal users, it began producing its own original content, competing head-to-head with legacy TV companies.

The result was that distributors became more powerful, seizing opportunities to acquire struggling traditional content creators. Time Warner was compelled to sell to AT&T, and Disney bought 21st Century Fox. Apple is following a similar path, building its Apple TV streaming platform and producing its own shows.

The New York Times is cautious about joining Apple News+, not only because third-party platforms might divert its readers, but also because these intermediaries disrupt the close and direct connection the Times has built with its audiences.

Apple News+ retains users within its own app rather than directing them to publishers’ websites. It also touts privacy protection as a key feature in two ways. First, Apple only tracks the clicking rate of each article on the platform, without knowing who reads what. Second, advertisers on the platform are prohibited from tracking user information, preventing them from targeting readers based on identities and reading habits.

This approach significantly weakens the profitability of traditional news outlets, making it difficult for them to provide value-added services to their audiences. Advertisers are also reluctant to partner with them because traditional ad-distribution models become ineffective.

“We want to email our readers and build relationships with them. We really don’t want anyone in the middle,” said Thompson. “The best relationship is building direct contact with readers.”

Revenue: Splitting Income with Tech Firms

Apple used to require legacy media outlets that joined the initial version of its Apple News platform to share advertising revenue with the company. Now, with Apple News+, it aims to take a cut of publishers’ subscription income as well.

Thompson emphasized the importance of media companies maintaining control over their business models and customer relationships when collaborating with tech firms. However, such collaborations have often resulted in unfavorable economic outcomes for publishers.

Under Apple News, publishers share ad revenue with Apple, which takes a cut of 30–50%. However, the Apple News+ service raises more concerns. Priced at just US$9.99 per month, it is significantly cheaper than a full New York Times digital subscription, which costs US$15. This pricing structure immediately puts media outlets at a disadvantage.

The revenue split is even more troubling. According to the Wall Street Journal, Apple claims half of all subscription revenue, redistributing the remainder to publishers based on factors like clicks and reading time—similar to how Spotify operates. For news organizations, a 50% cut is challenging to accept, especially considering that Apple charges app developers only 15% to 30% in its App Store.

Thompson did not elaborate on the specifics of the Times’ negotiations with Apple but highlighted the importance of partnerships that actively support the Times’ business model. He cited successful collaborations with Snapchat and Google that contributed positively to the Times’ growth.

“We created a custom visual product for Snapchat, and we also had a good financial agreement for both sides,” Thompson said. With Google, the platform adapted the Times’ paywall policies into its search engine and allowed readers access to three articles for free daily. This flexibility totaled 90 free articles accessible through Google, contrasting sharply with the Times’ standard policy of just five free stories per month through the paper’s website.

“Google accepted our paywall policies in its search engine, and we also collaborated to develop features that simplify the subscription process for our news through their platform. They understood our business model and recognized our needs. It’s a good and healthy partnership,” said Thompson.

Investment: Focusing on Quality Journalism

News organizations worldwide are struggling to transform their business models and adapt to new technologies. In 2011, The New York Times took a significant step away from its ad-dependent model by introducing a paywall and focusing on digital subscriptions. Thompson’s vision for future growth is straightforward: sustained investment in high-quality journalism.

“While most news organizations are cutting back, I don’t see how you can succeed by investing less in journalism,” Thompson said. He explained that the Times had been allocating more resources to its news and opinion sections, particularly in investigative reporting. His aim was to encourage greater collaboration among reporters on complex, cross-border stories, such as the tech revolution in Silicon Valley and China, or the competition between Boeing and Airbus, which often carry more profound geopolitical implications.

Thompson also placed high value on young readers. The Times’ podcast on Apple’s platform draws two million daily listeners, three-quarters of whom are under 40, and nearly half are under 30. “I believe millennials actually like classic brands. We have an edge over digital-native outlets in connecting young people with quality news,” he said.

The Times maintains journalists in 31 countries, frequently reporting from the front lines. Yet, many readers, especially younger generations, remain unaware of how news is made. Even U.S. President Donald Trump has accused the media of fabricating stories. In response, the legacy news organization decided to launch a weekly reality TV show beginning in June to demonstrate how its reporters cover the news.

Thompson and his team are committed to maintaining high standards in journalism while fully embracing digital transformation. They are betting boldly that high-quality content will win public support, strengthening the media’s competitiveness and negotiating power against tech platforms.

In February, the Times reported 2018 revenues of US$1.749 billion, up 4.4% year-over-year. Subscription revenues reached US$1.043 billion, accounting for 60% of the total income. Digital-only subscriptions generated US$401 million, an increase of 17.7% from the previous year.

With over 3.36 million digital product subscribers last year, including 2.71 million for digital news alone, Thompson has set an ambitious goal for the Times: to reach 10 million subscribers by 2025.